Fine of the Month: April 2007

(Ben Wild)

1. Images and Indexing: Scribal Creativity in the Fine Rolls, 1216–1234

In this month’s fine Ben Wild delves much deeper into the Fine rolls themselves and examines them as documents in their own right and their place in the workings of the Chancery and Exchequer. He asks to what extent roll headings, scribal references and cartoons were inspired purely by individual scribes and what role they played in the referencing system of English royal government.

1.1. Introduction

⁋1Though diverse, the extensive written output of England’s thirteenth-century government has two common characteristics: the style of script and the manner of composition. Documents of the Chancery, Exchequer and Wardrobe were all written in the same heavily abbreviated Latin cursive and conformed to proscribed templates. For almost every sort of legal action, royal command or exchequer account, there was a specific written form that scribes were expected to use. 1 Even diplomatic letters, conveying the king’s intimate concerns to a fellow potentate, had a standard structure. 2 The homogeneity of script and structure is, in one sense, a blessing. The bureaucratic output of England’s government is made instantly accessible. However, the overwhelming similarity of the documents also throws up problems: it can be hard to identify the work of individual scribes, or decide whether certain passages are later additions. In short, the task of understanding how the corpus of surviving material was collated, copied and used, can be a difficult one. 3

⁋2Thankfully, though, governmental scribes were never quite the photocopiers of their day. Scribes followed conventions in writing and enrolling, but when it came to indexing or labelling their work, exercised greater freedom. The fine rolls of Henry III (1216–1234) contain numerous examples of this scribal creativity. By looking at the cartoons and indexing codes on these rolls we can therefore pick up clues about thirteenth-century Chancery practice in England, and in the process, learn more about the development of the fine rolls.

⁋3Images taken from the first seventeen fine rolls of Henry III’s reign are available on this project’s website [from main page: Heads and Headings].

1.2. Headings

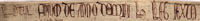

⁋1When looking at any sort of document it is natural, often essential, to study the heading first. Headings tell us what we are looking at. More than this though, headings indicate what a particular writer wanted us, as reader, to know upon first seeing their work. The heading of Henry III’s first fine roll is therefore very interesting. Written in large, narrow, capitals it is as follows: ROTULUS FINIUM ANNI REGIS HENRICI PRIMI, literally ‘Roll of fines of the first year of King Henry’. 4 The use of the ordinal ‘first’ is more than bombast. It seems to reveal the scribe’s sense of pride and excitement about the new reign, but, bearing in mind the fraught political climate in 1216, perhaps we can also sense trepidation. 5 Is this a confident claim, ‘the first of many’, or an ardent desire that this be so?

⁋2However, by the start of regnal year four (28 October 1219) the novelty of the fine rolls and the threat from within and without had faded. The heading of the fine roll for this year is simple and to the point: Rotulus Finium de Anno QUARTO iiijto. The capitalisation of ‘fourth’ and the use of Roman numerals smacks of bureaucratic efficiency, rather than idealism.

⁋3The tendency to simplify is also evident in the Chancery’s close rolls. The heading of the reign’s first close roll is: ROTULUS LITTERARUM CLAUSARUM REGIS HENRICI PRIMI, 6 and for the second: ROTULUS CLAUSARUM DE ANNO DOMINI H. REGIS FILII REGIS JOHANNIS SECUNDO. 7 In later years, however, the close roll headings are shorter, with a concern for clarity trumping individual expression. The heading for the twenty-fourth close roll is written thus: Clause de Anno Regni Domini H. Regis_____ Vicesimo_____Quarto_____. 8 The same is true of the patent rolls. The heading of the patent roll for regnal year two, written in stylised capitals, and this time endorsed, is: PATENTES DE ANNO DOMINI H. REGIS SECUNDO. 9 In contrast, the heading for regnal year five, also endorsed, is simply: PATENTES H. REGIS DE ANNO QUINTO Vto Vto. 10

⁋4Scribal attitudes cannot always be detected in these sort of changes however. In the Chancery’s liberate rolls, for example, there is often a great deal of variation in the headings. For regnal year thirty-four the heading is extremely detailed: Liberate et Contrabrevia, Computate et Allocate de Anno Regni Regis Henrici Filii Regis Johannis Tricesimo Quarto. 11 Similarly full headings are attached to the liberate rolls for regnal years fifty-four and fifty-six. And yet, liberate rolls for the years coming immediately before or after either have no headings, or very short ones. 12 The liberate rolls for regnal years four and twenty-one are also without headings, 13 and the heading for regnal year forty-two is simply: Liberate Anni xlij. 14 Generally, then, it would appear that a roll’s heading was governed less by a ‘house-style’ and rather more by a scribe’s discretion, which in itself says much about the differing attitudes and motivations of the Crown’s copyists.

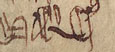

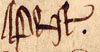

⁋5The use of sub-headings and marginal annotations in the fine rolls also enables us to see how the personal preference of one scribe could influence the decision of others. The third fine roll of Henry’s reign includes five monthly sub-headings, beginning with ‘MARCH’ 15 and going through to ‘OCTOBER’ 16 (there are no headings for June, August or September). The fourth fine roll contains a sub-heading for ‘APRIL’. 17 The decision to use monthly headings does not begin with the start of Henry’s regnal year (28 October), suggesting they were the brainchild of another scribe, writing later. However, after taking the first step and writing ‘MARCH’ in the margin of membrane 8, this scribe started a trend that others followed. That the monthly sub-headings were not the work of one scribe alone can be determined through palaeographical study. In ‘MARCH’, ‘APRIL’ and ‘MAY’ the letter ‘A’ is written very differently. In ‘MARCH’ the pen stroke which formed the cross bar of the ‘A’ is diagonal, sweeping upwards from left to right. In ‘APRIL’ the ‘A’ has no cross bar, 18 and in ‘MAY’ the ‘A’ has double, horizontal, cross-bars. 19 These differences provide sufficient warrant to say these headings were the work of at least three scribes. Furthermore, whilst the headings for ‘MARCH’, ‘JULY’ 20 and ‘OCTOBER’ are written in the left margin of the fine roll, those for ‘APRIL’, and ‘MAY’ are written in the main body of the text. Though helpful and useful in the eyes of some scribes, the innovation, for whatever reason, did not last.

⁋6Below is a full list of roll and month headings. Click on a thumbnail for a larger version of each image.

1.3. Symbols

⁋1The fact that Chancery scribes appear to have had a certain amount of creative licence, influencing other scribes in the process, should make us question the introduction and use of other marginal symbols and annotations on the fine rolls. Did the Chancery have a standard set of symbols that it used to flag queries or complex legal cases in its rolls? Or, as we saw above, did one scribe lead and others follow? 21

⁋2The following symbols appear in the fine rolls, down to 1234: ×, ÷, +, A and E. 22 The use of the mathematical division sign, ÷, was discussed by David Carpenter in the Fine of the Month for July 2006. 23 Whilst Carpenter showed that this symbol was used consistently to connect related entries (those who had fined to have their charters confirmed after Henry’s assumption of full regal powers in January 1227), it may not have had any special significance or meaning for the Chancery scribes: identical symbols frequently appear in different types of medieval record, but take on new meanings in each context.

⁋3Consider the wide and varied use of the symbol ‘З’. In the domestic diet accounts edited by Chris Woolgar, the ‘marginal sign З: in combination with a cash amount [was used] to indicate the surcharge on the corn and stock account’. 24 In manorial accounts, the same symbol was used to indicate the fictitious sale of goods that occurred at audit as a way of balancing the books. 25 The symbol also appears in a Wardrobe receipt roll for regnal year forty-nine, although quite what it means here, I don’t know. 26 None of these examples concern the Chancery, but practice was probably similar. We should also be aware that some of the scribes working for the Chancery might not have been regularly employed by the Crown. Michael Clanchy has shown that some Chancery documents were written by outside scribes, in the employ of barons or bishops, for example. 27 Different scribes undoubtedly had different training and techniques and this may well account for the changes noted above.

1.4. Heads

⁋1What, then, of the three images apparently of women that appear in the margin of the fine rolls? The first image appears to depict Mirabel, widow of Elias, Jew of Gloucester. According to her enrolled fine, Mirabel was instrumental in persuading William Marshal to uphold a grant of King John, which exempted her from inheriting her husband’s debts. 28 The second image is, perhaps, Hillary Trussebut, who received respite from rendering scutage. 29 The third image, if indeed it is female (no woman is mentioned in this or surrounding entries) must remain a mystery. If male, it could perhaps be Theodoric Teutonicus, the pledge of Waleran Teutonicus, who made a 200 m. fine to have the stanneries, die, mines and foundries of Devon for one year. 30 That all three images are so alike may suggest they served a common purpose or function: the women are all drawn in profile, facing away from the main body of text, and they all wear hats (albeit of different designs). The technique of drawing is also similar – look at the way the eyes are drawn, and the long, single pen-stroke, which forms the nose, mouth, and neck. Naturally, though, it is easier to suggest a connection than to determine one, and first impressions do not suggest that these fines were either particularly important or that the depiction of women was anything other than coincidence.

⁋2Between 1216-1234 the fine rolls contain 680 references to ‘wife’, 11 references to ‘Jewess’, and 270 references to ‘Jews’. There are at least three references to women acting as pledges, 31 and numerous fines deal with women’s debts. 32 One of these fines, that of Isabella de Bolbec, Countess of Oxford, was, on the face of it, far more lucrative and significant, than that dealing with Mirabel. Isabella made a £2228 2s. 9½d. fine for the custody of her late son’s lands; in addition, Isabella was expected to pay her son’s outstanding debts of £1778 11s. 33 A similar difference existed between the 200 m. (£133 13s. 4d.) fine that Waleran Teutonics made for the stanneries of Devon, and the 1000 m. (£666 13s. 4d.) proffered by John son of Richard and Stephen de Croy for the stanneries of Cornwall. 34 Quite why these larger and more substantial transactions were not highlighted when smaller fines were is puzzling. It is also worth noting that whilst an image draws attention to the first enrolment concerning Waleran Teutonicus’ fine, further enrolments dealing with his ownership of the Devon stanneries have no marginal annotations at all. 35 Nor do cartoons or symbols appear in the margins of the other Chancery rolls which mention Waleran in connection with the Devon stanneries. 36 Again, then, it would seem that the scribal discretion played a significant part in the creation of these cartoons.

⁋3What about images in other Chancery rolls, can these provide any clues as to why these fines were highlighted? Generally, images are few and far between in the Chancery rolls; I have only seen faces in the close roll for regnal year one, and again, there are no obvious indications as to why they are there. 37 Images are, however, more numerous in documents of the Exchequer. This is an important point. The Chancery rolls were implemented as an archival system, recording the concessions and orders of the king and, if we accept that John was as suspicious as some claim, control. As Vincent says of the Charter rolls, ‘by enrolling royal charters, the chancery supplied the king with a means of testing the authenticity of the privileges claimed from him by his subjects’. 38 The charter, close, liberate and patent rolls, then, did not really have a daily use. In contrast, documents of the Exchequer did. They helped sheriffs to collect the county farm, and provided the exchequer barons with the necessary information to conduct thoroughgoing investigations into the activities of almost every royal agent. In documents of the Exchequer one can see that marginal symbols and images served different and precise functions. Symbols (asterisks, crosses etc.) were ‘workaday’ marks, highlighting cases that needed to be checked or parts of a roll that had to be copied across to another document. In contrast, images drew attention to points of general interest that impacted on the custom, perhaps even the working ethos, of the Exchequer. Consider the use of images in the following examples taken from the Exchequer memoranda rolls.

⁋4In the memoranda roll for the Michaelmas – Trinty term 1267–68, a picture of a exchequer board is drawn next to a memorandum explaining how the barons had, against their custom (contra consuetudinem), remained in session until Friday 25 May to hear the account of Richard and William de Clifford, escheators beyond the River Trent. 39 This delay was most likely caused by the administrative chaos of the ‘disturbance of the realm’, this being the contemporary name ascribed to the period 1263–65 when the reformers and loyalists took to arms. 40 The note appears to have been added so as to make sure this sort of over-time would not set a new precedent. Here then, the picture did not serve any ‘daily’ function, but drew attention to an issue that everyone within the Exchequer felt strongly about (the note was enrolled at the behest of the treasurer and the barons). It was perhaps on similar grounds that a picture of King Edward I and Philip IV of France were drawn in the memoranda roll marking the truce of 1297, and in 1300, that a marginal picture of Edward highlighted a memoranda calling for the Exchequer to observe Magna Carta. 41 So how does help us determine the purpose of the three images in the fine rolls?

1.5. Conclusion

⁋1Well, firstly it suggests that, though products of the Chancery, the fine rolls were closer to Exchequer documents in terms of utility. Following on from this, comparison with Exchequer documents suggests that the three images were drawn as part of an internal dialogue within the Chancery of which the king and his council probably had little knowledge. By this I mean that, whilst having no great financial or political significance, the three cases appear to have had meaning for the Chancellor or his office. Whilst we may never know what specifically interested the Chancery in these cases, the three images nevertheless enable us to understand something about the complexities of compiling the fine rolls, and, offer a tantalising glimpse of how the Chancery functioned, as do all of the scribal marks that have been discussed here. We can only hope that the publication of the fine rolls down to 1272 tells us even more.

Footnotes

- 1.

- For examples, see, H. Hall ed., A Formula Book of English Official Historical Documents (New York, 1969), Part I: Diplomatic Documents, Part II: Ministerial and Judicial Records. Also, of course, Richard fitz Nigel’s Dialogus de Scaccario, (London, 1950), pp. 17–20, 28–34. There is no contemporary account of Chancery practice, but see, P. Chaplais, English Royal Documents: King John–Henry VI, 1199–1461, (Oxford, 1971). For specifics: on the whys and wherefores behind the introduction of the Chancery rolls in John’s reign see, N. Vincent, ‘Why 1199? Bureaucracy and Enrolment under John and His Contemporaries’; for an analysis of the Chancery’s development in the thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century see, D.A. Carpenter, ‘The Royal Chancery in the Thirteenth Century’, both papers are printed in A. Jobson ed., English Government in the Thirteenth Century (London, 2004), pp. 17–48 & 49–69 respectively. Also invaluable: M. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record, England 1066–1307, 2nd edition, (London, 1993), pp 62–78. Back to context...

- 2.

- Compare, for instance, Henry III’s letter to Frederick II describing the progress of the English forces against the French in 1242, with the military summons addressed to the sheriff of York in 1266, in, W.W. Shirley ed., Royal and other Historical Letters Illustrative of the Reign of Henry III, (London, 1866), 2 vols., ii, no. 434, pp. 25–29 & no. 649, pp. 300–02. The first letter, a personal communiqué between anointed sovereigns and former brothers-in-law, is a subtlely worded plea for help; the second, a letter close, is a direct royal command to summon the host. Despite this, both letters are similarly structured. Both letters open with a ‘cum’ clause (+subjunctive) which serves to set the scene (‘since …’) (p. 25, p. 300). This is followed with the request/order. In the letter close the king’s want is stated unambiguously, introduced with the rubric ‘[t]ibi praecipimus quod’ (p. 300) and ‘[t]ibi insuper praecipimus firmiter injungentes quod ... videris expedire’ (p. 301). In his letter to Frederick II, Henry is mindful that he addresses the Holy Roman Emperor and adopts softer-sounding verbs to suit, but note, the grammatical structure is unchanged, ‘Super his autem imperialem magnificentiam duximus certificandam, rogantes …’ ‘cupimus innotescere quod’ (p. 28). Back to context...

- 3.

- Of course, the flip-side is that changes to government documents can, on occasion, be identified more easily. See, D.A. Carpenter, ‘Chancellor Ralph de Neville and Plans of Political Reform 1215–58’, in his The Reign of Henry III, (London, 1996), esp. pp. 64–69. Back to context...

- 4.

- . Back to context...

- 5.

- For situation in 1216 see, D.A. Carpenter, The Minority of Henry III, pp. 1–49. Back to context...

- 6.

- C 54/16 m..25. Back to context...

- 7.

- C 54/18 m. 17. Back to context...

- 8.

- C 54/50 m.21. Back to context...

- 9.

- C 66/18, m.2. I was unable to look at the reign’s first patent roll when I visited TNA. Back to context...

- 10.

- C 66/24, m. 1. Back to context...

- 11.

- CLR 1245–51, p. 260. Back to context...

- 12.

- For example, for regnal year fifty-seven, Liberate de Anno Quinquagesimo Septimo, CLR 1245–51, p. 237. Back to context...

- 13.

- C 62/10, 11. Back to context...

- 14.

- C 62/34, m.5. Back to context...

- 15.

- CFR 1218–19, no. 168b. Back to context...

- 16.

- CFR 1218–19, no. 407b. Back to context...

- 17.

- CFR 1219–20, no. 123b. Back to context...

- 18.

- CFR 1218–19, no. 214b. Back to context...

- 19.

- CFR 1218–19, no. 243b. Back to context...

- 20.

- CFR 1218–19, no. 314b. Back to context...

- 21.

- The fine rolls contain some rubrics, ‘hinc mittendum est ad scaccarium’, for example. Back to context...

- 22.

- A further symbol is used in CFR 1219–20, nos. 24–25, apparently to indicate that the order of the enrolled entries should be swapped. Back to context...

- 23.

- In which, see n. 9. Back to context...

- 24.

- C.M. Woolgar, Household Accounts From Medieval England (Oxford, 1992) 2 vols., i, p. 42, and ii, where the symbol appears in the cash, corn, and stock account of Robert Waterton of Methley’s account, p. 519, n. 25. Back to context...

- 25.

- For example, if cattle died during the accounting period they could no longer be recorded among livestock, but nor could they just vanish. The solution was to record them in a separate section of the manorial account entitled ‘sales at the audit’ (vendiciones super compotum). P.D.A. Harvey ed., Manorial Records of Cuxham, Oxfordshire, circa 1200–1359, Historical Manuscript Commission, JP 23, (HMSO, 1976), pp. 51–54. See also, J.S. Drew, ‘Manorial Accounts of St. Swithun’s Priory, Winchester’, EHR, vol. 62, no. 42, (1947), p. 30. Back to context...

- 26.

- E 101/350/3. That is, for the keepership of Ralph of Sandwich between 1 January – 6 August 1265. Back to context...

- 27.

- Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record, pp. 57–58. Back to context...

- 28.

- CFR 1217–18, no. 17. Back to context...

- 29.

- CFR 1229–30, no. 114. Back to context...

- 30.

- CFR 1220–21, no. 86. Back to context...

- 31.

- CFR 1220–21, no. 108; CFR 1218–19, no. 281; CFR 1225–26, no. 158. Back to context...

- 32.

- For example: CFR 1217–18, no. 219; CFR 1219–20, no. 222; CFR 1221–22, no. 51; CFR 1226–27, no. 146; CFR 1227–28, no. 3. Back to context...

- 33.

- CFR 1221–22, no. 23. Back to context...

- 34.

- CFR 1220–21, no. 37. Back to context...

- 35.

- CFR 1221–22, no. 302; CFR 1222–23, no. 288. Back to context...

- 36.

- For example, C 66/24 m. 5. Back to context...

- 37.

- C 54/16, mm. 14/15. These images are not mentioned in Hardy’s edited volume, RLC, ii, p. 293. For that matter, marginal annotations/cartoons are not well documented in any of the printed Chancery rolls. Back to context...

- 38.

- Vincent, ‘Why 1199?’, p. 43; for examples of how the royal government used the Chancery rolls see, Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record, pp. 69–70. Back to context...

- 39.

- E 159/42, rot. 17d. Back to context...

- 40.

- For background see, J. R. Maddicott, Simon de Montfort, (London, 1994), chapters 7 & 8, pp. 225–345; M. Howell, Eleanor of Provence, Queenship in Thirteenth-Century England (Oxford, 1998), chapter 9, 206–30. Back to context...

- 41.

- E 368/69, rot. 54; E 368/72, rot. 12. Both images are printed in, M. C. Prestwich, Edward I, (London, 1997), plates 18 & 19. Back to context...