Fine of the Month: May 2009

(Carl Steward)

1. The Fine Rolls Project: A Study of Widows 1216–1234

As part of the MA in Medieval History at King’s College London, students frequently do studies based on the Henry III Fine Rolls Project and its website. As a example of this work, the Fine of the Month for May 2009 is by Carl Steward who is in his first year at King’s, reading for the MA part time.

1.1. Introduction

⁋1In the last two hundred years the English chancery rolls have been subject to several forms of publication. There was firstly the publication by the Record Commission of the earliest surviving rolls, namely those from the reign of King John. These were printed both in their original Latin and in a form of type (“Record Type”) which tried to imitate the original handwriting with all its abbreviations. Then the Public Record Office published the early patent rolls for the reign of Henry III together with the close rolls for the whole reign in full Latin but this time in modern type with the abbreviations expanded. The later patent rolls (those after 1232), meanwhile, together with the charter rolls and the liberate rolls, the Public Record Office published in English in an abbreviated form described as a ‘calendar’. All the volumes which resulted from these initiatives had indexes but these varied greatly in their extent and quality. 1 The Henry III Fine Rolls Project (henceforth FRP), which began in April 2005, offers a radically new form of publication. Its aim is to ‘to make the fine rolls for the reign of King Henry III available in as useful a form as possible to as many people as possible’. It attempts this by translating the rolls into English, and encoding them electronically so as to generate indexes and a search facility. All this is made freely available to everyone on the Project’s website. 2

⁋2This ‘Fine of the Month’ will begin by looking at the various benefits and problems encountered when using the FRP’s website. The essay will then show how the site can be used as a source for researching a general topic over a long period of time. It will do this by searching for widows in the search engine, producing a database from the resulting entries and showing how analysis from that database can be used as a starting point for many different areas of research regarding the early thirteenth century.

1.2. Benefits and Problems of the FRP

⁋1The accessibility of the FRP via the internet offers anyone, not just historians, the ability to look at and study the fine rolls of Henry III, one of the most important unpublished sources for the history of a formative period in English and British history. It is now possible to access the FRP via my mobile phone on the train home from university, through mobile broadband on my laptop in St. James Park or, God forbid, via Wi-Fi whilst eating a Big Mac in McDonalds.

⁋2A search on Google for ‘fine rolls’ has the FRP as the top two hits with a King’s College London page describing the FRP as the third hit. 3 A search for ‘Henry III’ on Google has the FRP as the sixth hit, behind two links to the BBC, and one each to royal.gov.uk, spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk and englishmonarchs.co.uk. 4 Clearly this demonstrates that the FRP is very easy to access. However, when I searched for ‘medieval sources online’, ‘medieval primary sources’ or ‘medieval chancery records’, the FRP did not appear. This is not altogether surprising considering the vague and general search terms used. I then tried to see if I could find a link to the FRP from the results of those searches. Even though the links included the Institute of Historical Research, British History Online and medievalgenealogy.org, I failed to find any mention of or link to the FRP.

⁋3This highlights a small fault of the FRP, in that only people who actually know what the fine rolls are, or, indeed, have even heard of the fine rolls will search for them online. Most non-historians struggle to name any medieval sources with the Magna Carta and Domesday Book as possible exceptions. By publicizing the fine rolls to a greater audience the FRP could encourage more people to become interested in medieval history and offer people ‘surfing’ for medieval sources the opportunity to look at a unique and fascinating source.

⁋4The FRP is very easy to use. The homepage is simple and is clearly laid out with a menu bar that includes a link to the search engine. The ability to search for a subject, a person or a place name makes it easy and quick to find entries. The thesaurus button next to the search engine is also a great idea. Not only does it help the user find the place or person being sought (if the exact details or spelling of that place or person are not known), but by listing the subjects, it allows users wanting to do a study based on the fine rolls easily to see potential categories of research (as I did with widows and this essay).

⁋5Despite its many advantages the FRP search engine does have some faults. Amanda Roper has identified an issue with the search engine with regards to place names. She points out that the search engine does not differentiate between place names that are actually involved in the context of the fine from place names that are where the fine was made. 5 That means that a search for ‘Winchester’ will show results for fines involving Winchester, fines for people from Winchester and for any fine that was made at Winchester. However, this problem can be rectified by using the indexes instead of the search engine. The FRP has three indexes, corresponding to a person, a place name or a subject in the same manner as the search engine. The indexes show which fines concern Winchester or people from Winchester as links to those directly follow the index. Fines made at Winchester, by contrast, are separated and categorised as ‘letters attested at’.

⁋6The indexes also provide greater clarity when searching for individual people, for example ‘William Marshal’ and ‘Hubert de Burgh’. Using the search engine produces a large number of entries that have nothing to do with William Marshall or Hubert de Burgh, but relate to them witnessing fines whilst they were regent or justiciar. However, the indexes distinguish between fines involving the person, fines where the person had a specific role and fines where the person was a witness. Another problem with the search engine is that some categories can be in two of the three search indexes (subject, person and place name) and those search indices produce a different number of results. For example, a search for widow in the person search index produces 214 entries whereas a search for widows in the subject search index produces 233 entries.

⁋7A possible criticism of translating primary sources onto the internet is that people will cease to view or use the original documents or facsimiles. That is why the FRP’s decision to scan digitally and display all the facsimiles on the website is a key and important part of the project. Having the facsimiles on the website offers many benefits for researchers. It allows them to view the facsimile and its translation, as well as the variants of place and personal names modernised in the translated text, at the same time in an easily accessible place. That saves a great deal of time and money by not having to go to The National Archives in Kew every time an original roll needs to be checked. By displaying the facsimiles on the internet, for the use of anyone, the FRP can allow students of palaeography and Latin access to a wealth of texts that they can use as study aids or for practice. 6

1.3. Analysis of Widows Entries in the Fine Rolls

⁋1The clerks who drew up the fine rolls divided them up into separate entries, most often marked off from each other by the ‘¶’ symbol, and these entries have each been given a separate number in the translation prepared by the Project. Since each entry usually referred to a writ (for example one ordering the sheriff to take security for the payment of a fine) and since the date and place of the issue of the writ was usually recorded, it is possible to date most of the entries and see where the decisions they recorded were made. 7 The search facilities provided by the FRP allow this and other information to be accessed. That information can be recorded quickly and easily on a spreadsheet to produce a database for entries concerning widows. Appendix A is a section of the database I produced. It shows the entries’ regnal year and the number of the entry for that year, the date of the entry, a summary of the entries’ content and purpose, how much any fine recorded in the entry was for, the place where the entry was made and finally the county to which it related.

⁋2The database has a total of 233 entries. These were found when the subject ‘widows’ was typed into the search engine of the FRP. This is only 3.7% of the total number of entries for 1216-1234. 8 Far from all these entries refer actually to fines. 39 of the 233 simply repeat previous entries, with the majority in the format of “It is written in the same manner to the sheriff of X”. 9 A further three entries are unfinished. By discounting those 42 entries the remaining 191 entries lower the percentage of entries concerning widows to 3%.

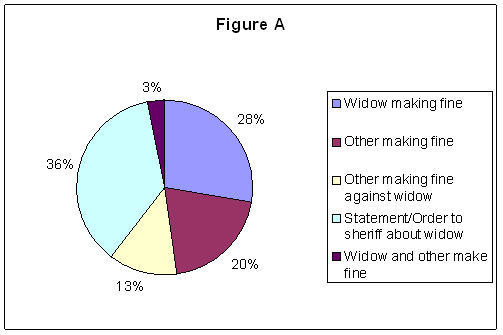

⁋3This small percentage suggests that not many widows resorted to petitioning the king for favours. That is highlighted even further by figure A which breaks down the 191 widows’ entries into five categories determined by the subject of the fine. It shows that only 28% of the 191 entries concerning widows actually relate to an individual widow making fine. Even if the 3% from the fines relating to widows making fines with another individual or as part of a group is added to the 28%, widows making fines are not the most frequent category of entry in the database. Orders to sheriffs and statements or grants from the king that concern widows provide over a third of the total entries. Fines concerning widows made by lords, freemen and occasionally women account for 20% of the total, with a further 13% of fines being made against widows.

-

- Figure A

⁋4Figure A shows that only 31% (28% from individual widows making fine and 3% from widows making fine as part of a couple or group) or 59 of the 191 entries concerning widows actually involve widows making fines themselves. That represents less than 1% of the 6332 total entries made between 1216 and 1234. This small figure offers the historian a puzzling conundrum. Does the small figure show that widows were well treated and therefore rarely needed to make fine with the king over grievances? Or does it suggest that widows saw little point in trying to resolve their grievances by making fine?

⁋5Many historians have argued that widowhood offered advantages to women of the nobility. Shulamith Shahar writes that ‘A widow who was well provided for enjoyed greater freedom than any other type of woman in medieval society’. 10 Susan Johns claims that medieval noble widows were enfranchised to a much greater degree than married or unmarried women. 11 That could be why a small percentage of fines involve widows. However, in a study of widows in the fine rolls, Susanna Annesley concluded that widows often found themselves at the mercy of a male overlord. Annesley used individual fines during the period 1216–1225 to highlight the problems widows faced with dower, remarrying and wardship. 12 The debate over the hardships or benefits of widowhood is just one of many areas in which the FRP can be used as a starting point for further research. 13

⁋6Appendix B shows the 191 entries categorised by the type of entry. For example, a lord makes a fine to marry a widow. The most striking finding is the fact that there is no one type of entry that dominates the results. It seems that widows made fines for many different reasons. However, there are two main areas of fines, those related to the marriage of a widow and those related to a widow’s dower or land. It is on the fines related to the marriage of a widow that we will now focus.

⁋7Fines related to the marriage of a widow appear in three different categories of fines; fines by widows so they can choose whom they marry, fines by lords and widows who married without the king’s license and fines by lords to marry a widow. Appendix C shows the entry numbers, the date, the amount paid and any additional information for the ‘choose who they marry’ and ‘married without king’s license’ fines. There is a striking contrast between the two categories of fines in relation to their dates. Twelve out of the fifteen ‘choose who they marry’ fines are found between 1226 and 1234. By contrast, nine out of eleven ‘married without king’s license’ fines are found between 1216 and 1226.

⁋8This suggests a relationship between the two. When a small number of widows are fining for the right to marry who they choose, a larger number are being fined for marrying without a license. Similarly, when a large number of widows are fining for the right to marry, there seems to be a drastic reduction in the number of fines for marrying without the king’s license. This relationship should not be a surprising one. If more widows are fining for the right to marry, then clearly there will be fewer who can be caught married without the king’s license and vice versa. Scott Waugh argues that the king was very efficient in finding out if his tenants had married without a licence. He claims that it would have been very unlikely that the king would not find out about a marriage of one of his tenants, as news and rumours of marriages reached his court in many ways. 14

⁋9The increase in widows fining to choose whom they marry and the decrease in fines for marrying without the king’s license both occur around 1226. That date coincides with two important events in the early years of Henry’s reign. On 11th February 1225 Henry re-issued the 1217 ‘Magna Carta’, “of his own free good-will”. 15 On 21 January 1227 in a circular letter to all his sheriffs Henry states that he will cause charters and confirmations to be made under his seal. 16 Essentially this ended his reign as a minority king. Could either Henry’s assumption of full regal powers or the re-issuing of Magna Carta be the stimulus for the changes seen in the fine rolls around 1226 regarding the marriage of widows? 17

⁋10In a writ from 1243, Henry showed his anger towards widows remarrying without consent where he stateed that widows had spurned the security that they were supposed to give not to marry without consent, had not asked for consent, and had married themselves indiscriminately to whomever they pleased. 18 Perhaps Henry sought to redress that when he finally came of age in January 1227? However, the writ was written sixteen years after the beginning of Henry’s majority and its content claims that many widows were still marrying without consent, which goes against the evidence that the database suggested.

⁋11Clause eight of Magna Carta states that ‘No widow shall be forced to marry … provided that she gives security not to marry without our consent’. 19 This statement is very clear and the great decrease in widows making fines for marrying without consent after 1225 may be viewed as a sign of increased compliance with the Charter or possibly a greater attempt by sheriffs to enforce it. There is further evidence of greater compliance with Magna Carta in the evidence from the entries on lords paying fines to marry a widow. Annesley in her study of widows in the fine rolls attempted to establish the degree to which clauses seven and eight of Magna Carta were being obeyed between 1216 and 1225. She rightly claimed that two entries from 1218 and 1219 were ‘anomalies’ as they state that a lord may take a widow to marry ‘if she gives her consent’. However, she then goes on to claim that ‘Nowhere else in the decade covered by this paper is any widow’s consent specifically referred to again’. 20

⁋12The period covered by her paper stopped just short of an entry that does in fact refer to the consent of a widow. Entry 9/370 dated 24th October 1225 states: ‘Thomas de Venuz has made fine with the king by 10 m. for having to wife Isabella, who was the wife of Robert Mauduit. Order to the sheriff … he is to permit Thomas to have Isabella as his wife if she will consent to this.’ 21 There follows after this ‘extra anomaly’ a further five fines where lords fine to marry a widow, none of which mention consent. Therefore, in the period 1216–1234 there are only three entries which mention consent. 22 Two of those come shortly after the re-issuing of Magna Carta in 1217 and the other one comes shortly after the re-issue of Magna Carta in 1225. It is possible that consent was not mentioned in other fines because the government already knew that it had been given and so therefore it was not necessary to record. However, the timing of the fines that do mention consent back up the idea that greater compliance, more efficiency and a stricter following of Magna Carta’s clauses are seen directly after a re-issuing of Magna Carta.

1.4. Analysis of where entries were made and where they were for

⁋1Appendix D shows the 53 different places where the king or justiciar were when an entry was made during 1216–1234. It shows the dominance of Westminster as a residence for the king as almost half of the entries were made at Westminster. It also shows that the king or justiciar had no ‘second favourite’ place of residence as no other place has more than seven entries made at its location in the sixteen year period. Finally, it suggests that the king and/or justiciar were widely travelled. Discounting entries made at Westminster, the remaining 101 were made at 52 different locations.

⁋2The 191 entries that concern widows from 1216–1234 deal with widows from almost all of the counties of England. 23 It has already been established that the majority of entries were made at Westminster. To travel to and from Westminster would be a time consuming and expensive journey for someone travelling from Cornwall, Cumberland or even Ireland. Is there any evidence that people furthest away from Westminster were more likely to wait for the king to visit closer to them (for example, York for people in Cumberland, Northumberland and Yorkshire, or Gloucester for people from Devon and Cornwall) before they made fine or were they content to travel long distances in order to make their fine?

⁋3Appendix E shows the different counties with their total number of entries, the number that were made in Westminster and the number that were made elsewhere. It shows that there is no evidence that people from counties further away were making fewer fines at Westminster. The majority of counties have a roughly even number of entries made at Westminster and elsewhere. The counties that only have entries at Westminster include Cornwall, Hertfordshire, Suffolk and Surrey. The counties that only have entries at places other than Westminster include Berkshire, Cumberland, Gloucestershire and Huntingdonshire. Although the sample size of this data is significantly small the overall impression is that people were perfectly willing to travel long distances to make their fines.

⁋4There are 101 entries that were not made at Westminster. Only fourteen of these entries have the place where the entry was made in the same county that the entry relates to. This evidence backs up the argument that people travelled long distances in order to get their fines made. However, the data is not complete as from 1224 and more regularly from 1226 the fine roll clerks began to enter the subject or the person of the fine instead of the county in the marginalia. Of the 101 entries that were not made at Westminster, nineteen stated the subject or person and two entries did not state either a county or a description. Seven of the nineteen entries can have the county they relate to worked out, as the content mentions an order to the sheriff of the relevant county. 24 The other twelve subject or person entries either have no mention of an order, or have an order to the barons of the exchequer or Peter de Rivallis. 25

⁋5The earliest entry relating to a widow that has a subject or person rather than a county in the marginalia is CFR 1223–24, no. 343. from 30th August 1224, however, entries with subjects or people become more regular only after entry CFR 1225–26, no. 196 from 19th June 1226. David Carpenter gives a detailed description of the change in marginalia in the historical introduction on the FRP website. He argues that subject/person entries begin to be seen in the 8th year of Henry’s reign 1223–24. Carpenter highlights two possible causes of the change in marginalia – the need to identify individual people in the Falkes de Breaute affair and the desire of Ralph de Neville to reform the fine rolls in line with other rolls. 26 The change in marginalia also seems to have a sense of logic behind it, as entries with the subject or person in the marginalia tend to be orders to sheriffs or other officials, whereas entries with the county in the marginalia are generally straightforward fines. It is interesting that clerks begin to change how they formulate a fine roll entry at roughly the same time as the increase in widows fining to choose who they marry and the decrease in fines for marrying without the king’s license begins to happen. This could show that between 1224 and 1226 there were significant steps made to make the procedure of making fine more efficient.

1.5. Analysis of where entries were made and where they were for

⁋1The suggestion of an increase in efficiency in government around 1224 to 1226 is one of the many areas in which this essay has shown that a database created from the results of a search on the fine rolls projects search engine can act as a starting point for further research. It has shown that very few of the entries found in the fine rolls concern widows and out of those that do less than a third actually involve widows themselves making fine. That information can be used for debates concerning the benefits or hardships faced by women during widowhood. Appendices B and C have shown that there were many different contexts in which widows made fines and no one context dominates the entries.

⁋2The fine rolls can also tell us about the relationship between the location of the king and the process of making fine. The fact that the majority of entries state where the entries are for and where they are made (or those facts can safely be assumed), allows research into people’s ability and willingness to travel to make fines. Appendix E has shown that people had no problem in travelling long distances to make fines. A more detailed survey using all the entries not just those concerning widows could inform this argument to a greater degree. Appendix D highlights the dominance of Westminster in regards to where the king resides. It also shows that when the king is not at Westminster he stays at many other places and is often travelling from place to place. Further research could also be carried out regarding this area, again by using all the fine rolls entries not just those concerning widows.

⁋3The fine rolls website is free to use and easy to access through internet search engines. The inclusion of its own search engine is one of the most important aspects of the FRP as it makes researching the fine rolls much quicker than researching via a book. The maintaining and displaying of the original records, retains a relationship with the past whilst allowing greater access to these important and beautiful documents. The FRP plays a significant role in the history of the way in which primary sources are recorded and translated. One day, a student of the future might be able to access and look on a search engine for not only fine rolls entries but also information about their category on charter rolls, close rolls, liberate rolls or any of the many fascinating chancery records that exist. The ability to search quickly over a vast amount of sources could revolutionise the way a scholar researches history allowing greater studies over wider areas and longer time periods. The internet and the use of search engines are the future for the way we interpret and record the documents of the past and the FRP is an excellent example for other projects to follow.

2.1. Appendix A: An Example of the Database of the 233 Entries Concerning Widows

| Reference | Date | Subject | Amount | Place of witness | County |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3/56 | 9/12/1218 | widow fines for having a pone | 6s. 8d. | Tower of London | Oxfordshire |

| 3/114 | 20/1/1219 | widow fines to summon someone before the justices for them to pay her 3½ m | 6s. 8d. | Westminster | Lincolnshire |

| 3/141 | 5/2/1219 | woman gives fine for a pone with a widow as one of the claimants | 6s. 8d. | Westminster | Cambridgeshire |

| 3/143 | 9/2/1219 | 4 men fine to be handed over to law-worthy men and for an appeal by a widow whose husband she claims they killed | 20s. | Westminster | Staffordshire |

| 3/206 | 22/3/1219 | order to sheriff to get pledges for lord’s fine because he married a widow without the king’s leave | 5 m. | Caversham | Bedfordshire |

| 3/210 | 22/3/1219 | lord fines for having a pone of a plea between him and a widow | 6s. 8d. | Caversham | Wiltshire |

| 3/213 | 26/3/1219 | lord gives fine for having a writ to summon 12 jurors against a widow | 6s. 8d. | Caversham | Cambridgeshire |

| 3/217 | 2/4/1219 | widow gives 4th part of a debt in order to summon 4 men before the justices to answer for money they owe her | unspecified | Caversham | Devon |

| 3/233 | 18/4/1219 | lord fines to have a pone before justices against a widow | 6s. 8d. | Oxford | Northamptonshire |

| 3/242 | 27/4/1219 | woman gives fine for a pone against a widow | 6s. 8d. | Westminster | Suffolk |

| 3/320 | 3/7/1219 | 2 men fine to be handed over to law-worthy men and stand before a court for the death of a widow’s clerk | 1 m. | Hereford | Gloucestershire |

| 3/321 | 3/7/1219 | order to sheriff to give widow her dower lands and take the rest into the king’s hands and keep them safe | no fine | Hereford | Essex |

| 3/322 | 3/7/1219 | 2 men fine to be handed over to law-worthy men and stand before a court for the death of a widow’s clerk/a man | 1 m. | Hereford | Gloucestershire |

| 3/324 | 6/7/1219 | widow fines to have a writ against a lord for a tenement | 6s. 8d. | Westminster | Oxfordshire |

| 3/367 | 18/8/1219 | man fines to have a widow as his wife if she gives assent | 6 palfreys | Oakham | Buckinghamshire |

| 3/368 | 18/8/1219 | regarding above (3/367) stating the same to sheriff of Berkshire | 6 palfreys | Oakham | Buckinghamshire |

| 3/378 | 24/8/1219 | lord fines for having an exchange of land with a lord who died and the widow now claims that land as her dower | 6s. 8d. | Grantham | Lincolnshire |

| 3/403 | 24/9/1219 | man fines to be handed over to 12 law-worthy men for an appeal over a widow’s husband’s death | 1 m. | New Temple, London | Yorkshire |

| 4/19 | 23/11/1219 | lord fines for taking widow as his wife | 2 palfreys | Hereford | Herefordshire |

| 4/84 | 10/2/1220 | lord fines to king for having married without licence, all lands to be restored and marriage allowed | 100 m. | Westminster | Derbyshire |

| 4/85 | 10/2/1220 | Same as (basically repeating) 4/84 | 100 m. | Westminster | Derbyshire |

| 4/89 | 11/2/1220 | Same as (basically repeating) 4/84 | 100 m. | Westminster | Derbyshire |

| 4/120 | 14/3/1220 | man fines to be handed over to 12 law-worthy men to stand trial over a widow’s husband’s death | 20s. | Hinxton | Cumberland |

| 4/148 | 11/5/1220 | widow fines to summon lord over land she claims as her marriage portion | 6s. 8d. | Westminster | Devon |

| 4/175 | 15/6/1220 | widow fines for having justice aginst a dean who she claims has taken her chattels | 10 m. | Oxford | Yorkshire |

| 4/222 | 9/8/1220 | order that a widow is to receive her husband’s corn revenues so long as she pays debts to the king owed by her husband | no fine | Wilton | Cambridgeshire & Huntingdonshire |

| 4/263 | 12/9/1220 | widow and new husband fine for her dower | 100 m. | Westminster | Ireland |

| 5/7 | 4/11/1220 | lord fines to have custody of lands and heirs save the dower of the widow | 500 m. | Westminster | Herefordshire |

| 5/8 | 4/11/1220 | terms of payment for 5/7 | 500 m. | Westminster | Herefordshire |

| 5/12 | 9/11/1220 | widow fines for having a pone against man concerning land | 6s. 8d. | Westminster | Herefordshire |

| 5/21 | 17/11/1220 | order to seize widow’s lands as she married without king’s licence | no fine | Westminster | Somerset & Dorset |

| 5/22 | 17/11/1220 | Same as 5/21 ordered to different sheriffs | no fine | Westminster | Somerset & Dorset |

| 5/41 | 28/11/1220 | order to keep in king’s hands lands of deceased lord and to cause his widow to be reasonable supported | no fine | Canterbury | Unspecified |

2.2. Appendix B: Context of the Entries 27

| Context of Entry | Amount of Entries |

|---|---|

| Same as above but to different sheriff/place | 39 |

| Other | 34 |

| Widow giving fine to marry who she chooses | 16 |

| Someone gives fine for a pone involving a widow | 15 |

| Widow makes fine for Custody of land and heir, inc. marriage of heirs | 14 |

| Lord giving fine to marry widow | 12 |

| Widow/Lord receiving respite | 12 |

| Someone gives fine for a writ involving a widow | 12 |

| King gives land to widow (so she can answer to him for it) | 12 |

| Fine for marrying without licence | 11 |

| Widow involved in court case over death of her husband | 10 |

| Man/Lord/Group gives fine for seisin saving rightful dower to widow | 9 |

| Order to sheriff to take lands and give widow her dower | 9 |

| Widow involved in court case over money | 6 |

| Lord makes fine for Custody of land and heir, inc. marriage saving dower | 5 |

| Widow involved in court case over rights of land | 4 |

| Widow gives fine for knight’s fee | 4 |

| Lord gives fine for letters patent | 3 |

| Fines involving Falkes | 3 |

| Entry concerning dead widow’s land | 3 |

| Entry unfinished | 3 |

| Widow/lord makes fine for Custody of land and heir | 2 |

2.3. Appendix C: Fines Related to the Marriage of Widows

2.3.1. Fines for a widow to marry who she chooses

| Entry number | Date | Amount | Other things for which fine is made |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2/88 | 17/5/1218 | 5 m. | |

| 5/179 | 25/5/1221 | 100s. | |

| 6/111 | 13/2/1222 | 20 m. | |

| 10/158 | 3/5/1226 | 100 m. | |

| 11/125 | 3/3/1227 | 100 m. | Dower |

| 13/187 | 2/5/1229 | 5 m. | Inheritance |

| 13/325 | 30/9/1229 | 200 m. | Quittance from sending knights and scutage |

| 13/500 | 15/10/1229 | 100 m. | |

| 14/258 | 17/4/1230 | 25 m. | |

| 15/339 | 23/10/1231 | 700 m. | Inheritance |

| 16/17 | 2/12/1231 | 100 m. and palfreys | Custody of land and heirs with their marriage |

| 17/21 | 13/11/1232 | 300 m. | Dower |

| 17/109 | 4/2/1233 | 2 palfreys | |

| 18/151 | 26/1/1234 | 40 m. | The fine is for a widow’s daughter to marry whom she will |

| 18/226 | 22/6/1234 | 60 m. | £500 (19%) |

2.3.2. Fines for marrying without the king’s licence

| Entry number | Date | Amount | Other things for which fine is made |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3/2 | 30/10/1218 | 5 m. | Son pays fine to his widowed mother, as she held his licence to marry |

| 3/19 | 9/11/1218 | 100s. | |

| 3/206 | 22/3/1219 | 20 m. | |

| 4/84 | 10/2/1220 | 100 m. | Lands restored and marriage allowed |

| 5/21 | 17/11/1220 | 100 m. | Widow’s lands to be seized |

| 5/88 | 11/2/1221 | 5 m. | |

| 6/211 | 27/6/1222 | 200 m. | Lords lands to be seized |

| 8/421 | 23/10/1224 | 100 m. | Lands restored and marriage allowed |

| 10/343 | 17/10/1226 | 25 m. | Dead lord and his widow’s lands to be seized as widow permitted daughter/heiress to marry without the king’s licence |

| 14/462 | 9/1230 | 700 m. | Lord’s lands to be seized |

| 18/342 | 7/11/1234 | 100 m. and palfreys |

2.4. Appendix D: Places entries were made

| Where entry was witnessed | Number of entries |

|---|---|

| Bedford | 1 |

| Bosham | 1 |

| Brackley | 1 |

| Bridgnorth | 1 |

| Brill | 1 |

| Burgh next Aylsham | 1 |

| Canterbury | 2 |

| Castle Bytham | 1 |

| Caversham | 4 |

| Cirencester | 1 |

| Does not say | 1 |

| Dover | 1 |

| Evesham | 1 |

| Gloucester | 4 |

| Grantham | 1 |

| Havering | 1 |

| Hereford | 7 |

| Hinxton | 1 |

| Kerry | 1 |

| Kingston upon Thames | 1 |

| Lambeth | 2 |

| London | 2 |

| Marlborough | 2 |

| Marwell | 1 |

| Morton | 1 |

| New Temple, London | 1 |

| Nottingham | 3 |

| Oakham | 1 |

| Odiham | 1 |

| Oxford | 2 |

| Painscastle | 2 |

| Portsmouth | 5 |

| Reading | 3 |

| St. Albans | 2 |

| St. Edmunds (Bury) | 1 |

| St. Paul’s, London | 1 |

| Sandford | 1 |

| Strigoil (Chepstow) | 1 |

| Tewkesbury | 2 |

| Tower of London | 4 |

| Wallingford | 1 |

| Waltham | 1 |

| Waverley | 2 |

| Westminster | 90 |

| Weston | 2 |

| Wetherby | 1 |

| Wilton | 1 |

| Winchester | 5 |

| Windsor | 1 |

| Woodstock | 4 |

| Worcester | 3 |

| York | 3 |

2.5. Appendix E: Counties where entries were for and whether they were made at Westminster or elsewhere

| County | Number of entries | Court at Westminster | Court in county which entry concerned | Court elsewhere | Does not say |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedfordshire | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Berkshire | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Buckinghamshire | 8 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Cambridgeshire | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Cornwall | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cumberland | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Derbyshire | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Devon | 7 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Dorset | 6 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Essex | 11 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Gloucestershire | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Hampshire | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Herefordshire | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hertfordshire | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Honour of Richmond | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Honour of Wallingford | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Huntingdonshire | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Ireland | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Kent | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Leicestershire | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Lincolnshire | 12 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Norfolk | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Northamptonshire | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Northumberland | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Nottinghamshire | 8 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Oxfordshire | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Somerset | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Staffordshire | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Suffolk | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Surrey | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sussex | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Warwickshire | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Wiltshire | 8 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| Yorkshire | 13 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Does not say | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Other | 35 | 16 | N/A | 19 | 0 |

Footnotes

- 1.

- For the earliest chancery rolls see N. Vincent, ‘Why 1199? Bureaucracy and Enrolment under John and his Contemporaries’, in A. Jobson (ed.), English Government in the Thirteenth Century (Woodbridge, 2004), pp. 17–48 and in the same volume D.A. Carpenter, ‘The English Royal Chancery in the Thirteenth Century’, pp. 49–69. Back to context...

- 2.

- FRP website: http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/cocoon/frh3/content/about/proj_aims.html, (accessed 13/04/09). Back to context...

- 3.

- Google Search Engine: http://www.google.co.uk/search?hl=en&safe=off&q=fine+rolls&meta=, (accessed 13/04/09). Back to context...

- 4.

- Google Search Engine: http://www.google.co.uk/search?hl=en&safe=off&q=henry+iii&btnG=Search&meta=cr%3DcountryUK%7CcountryGB, (accessed 13/04/09). Back to context...

- 5.

- Amanda Roper, Medieval History and the Internet: the Henry III fine rolls project, the Fine of the Month for April 2008 (accessed 13/04/09). Back to context...

- 6.

- Roper, Medieval History and the Internet. Back to context...

- 7.

- Those entries which are not dated in the original have been silently given the date and place of witness of the previous dated entry in the roll. See the Project’s Style Book for further details. Back to context...

- 8.

- There are 6332 total entries for the years 1216–1234. Back to context...

- 9.

- For example, Calendar of the Fine Rolls of the Reign of Henry III [henceforth CFR] 1220–21, no. 22 (available both on the Henry III Fine Rolls Project’s website and within Calendar of the Fine Rolls of the Reign of Henry III 1216–1234, ed. P. Dryburgh and B. Hartland, technical ed. A. Ciula and J.M. Vieira (Woodbridge, 2007), p. 174. Back to context...

- 10.

- Shulamith Shahar, The Fourth Estate: A History of Women in the Middle Ages, translated by Chaya Galai, (London, 1983), p. 95. Back to context...

- 11.

- Susan M. Johns, Noblewomen, Aristocracy and Power in the twelve century Anglo-Norman Realm (Manchester, 2003), p. 175. Back to context...

- 12.

- Susanna Annesley, ‘The impact of Magna Carta on widows: evidence from the fine rolls 1216–1225’, the Fine of the Month for November 2007 (accessed 13/04/09). Back to context...

- 13.

- See David Carpenter, ‘Hubert de Burgh, Matilda de Mowbray and Magna Carta’s Protection of Widows’, the Fine of the Month for March 2008 (accessed 13/04/09) and Michael Ray, ‘The lady is not for turning: Margaret de Redvers’ fine not to be compelled to marry’, the Fine of the Month for December 2006. Back to context...

- 14.

- Scott. L. Waugh, The Lordship of England: Royal Wardships and Marriages in English Society and Politics 1217–1327 (Princeton, 1988), p. 216. Back to context...

- 15.

- Kate Norgate, The Minority of Henry the Third (London 1912), p. 250. Back to context...

- 16.

- Norgate, The Minority of Henry the Third , pp. 265–66. Back to context...

- 17.

- For a more detailed analysis of Henry III’s assumption of full regal powers see Sophie Ambler, ‘The Fine Roll of Henry III 28th October 1226–27th October 1227’, the Fine of the Month for December 2007 (accessed 13/04/09). Back to context...

- 18.

- Waugh, Lordship of England, p. 68; Close rolls of the reign of Henry III preserved in the Public Record Office / printed under the superintendence of the Deputy Keeper of the Records: Vol.5, (1242–1247) (London, 1916), p. 61. Back to context...

- 19.

- ‘The 1217 Magna Carta’, in H. Rothwell (ed.), English Historical Documents 1189–1327 (London, 1975), p. 333. Back to context...

- 20.

- Annesley, ‘The impact of Magna Carta on widows’. Back to context...

- 21.

- CFR 1224–25, no. 370. Back to context...

- 22.

- CFR 1217–18, no. 72; CFR 1218–19, no. 367; CFR 1224–25, no. 370. Back to context...

- 23.

- Middlesex, Shropshire and Worcestershire are the only counties not to have a fine. Back to context...

- 24.

- For example CFR 1223–24, no. 403. Back to context...

- 25.

- For entries with orders to the barons of the exchequer see CFR 1225–26, no. 196; CFR 1232–33, no. 365. For entries with orders to Peter de Rivallis see CFR 1231–32, no. 272. CFR 1232–33, no. 60. Back to context...

- 26.

- ‘Historical Introduction’, FRP website: http://www.finerollshenry3.org.uk/cocoon/frh3/content/about/historical_intro.html, (accessed 16/06/09). The other rolls referred to are the patent and close rolls. Back to context...

- 27.

- Five entries fall into two categories, so the total amount of fines is 238 not 233. Back to context...